During this special period, which culminates in the fast and mourning of the 9th of Av — the day of the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple — Jews around the world focus on studying subjects connected to the Beit HaMikdash. Learning the laws, details, and deeper meanings of the Holy Temple during this time is not just a remembrance of the past, but a meaningful step toward its future rebuilding.

As stated in Midrash Tanchuma, studying the design and structure of the Temple is considered by G-d as if one is actually building it. The Rebbe emphasized that especially during the days leading up to the 9th of Av, our focus should not only be on mourning the loss but on “living” the future redemption — by strengthening our faith, hope, and knowledge of the Temple and its service.

In this spirit, our site presents a selection of texts to be studied during these days. They include historical overviews, detailed explanations of the Temple Mount and its structure, and insights into the spiritual essence and significance of the Temple for every Jew.

The Holy Temple

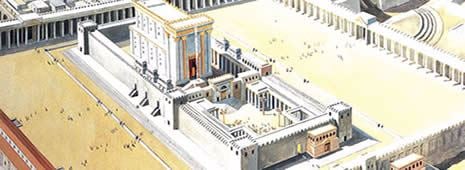

The Holy Temple (Beit Hamikdash) was a large structure that was the nucleus of Judaism, its most sacred site. It stood atop Jerusalem’s Mount Moriah. Our people would stream there three times a year to bring sacrifices and interface with the Divine.

The first Beit Hamikdash was built by King Solomon in the year 833 BCE, and destroyed by the Babylonians in the year 423 BCE. The second Beit Hamikdash was completed in the year 349 BCE by Jewish returnees from the Persian exile, renovated by King Herod in 19 BCE, but ultimately destroyed by the Romans in 69 CE, when the current galut (exile) began.

For nearly 2,000 years, there has been no Holy Temple in Jerusalem. Yet, it is an axiom of Jewish belief that the Temple will be rebuilt in Jerusalem. Known as the Third Temple, it will be built according to the prophecies of Ezekiel.

Har Habayit – The Temple Mount

At the time of King Solomon this mountain was 500 x 500 cubits. It had 5 points of entry:

South – Two Chuldah gates.

West – The Kiphonus gate.

North – The Tadi gate.

East – The Shushan gate.

(King Herod, who extended the Temple Mount area, added 3 additional gates to its western side.)

The focal point of the Temple Mount was a central courtyard containing the structure of the Bet Hamikdash. The rest of the Temple Mount area contained various rooms and buildings, including:

• House of Study, in which the Talmudic law was taught and discussed.

• Lounge for minor Temple officials.

• Weapons room, in case of enemy invasion.

• Tool room for repair work.

• Trumpet place. The shofar (ram’s horn) was sounded from the roof of this building before the onset of the Sabbath to let the people know when they must refrain from work.

Chuldah Gates

These were the main doorways used to access the Temple mount, one gate was used as the entrance, while the other gate served as an exit.

The Prophetess Chuldah, would sit near this area during the final years of the first Temple, admonishing Jewish women to give up their idolatrous ways. When the Second Temple was built, these gateways were named after her.

Kiphonus Gate:

This gate took the visitor through a tunnel which led to the top of the Temple Mount. Near the outside of the gateway was a magnificent garden with many types of roses used in the compounding of the Temple incense – hence the name Kiphonus – rose garden in Greek.

Tadi Gate:

All the Temple gateways shared the same basic rectangular design. The Tadi gate, however, had a unique triangular shape. The name Tadi comes from the Greek word meaning “high”. The angle formed at the top made this doorway higher or taller than the others.

Shushan Gate:

The Eastern Temple Wall had one gateway called the Shushan Gate. The Persian emperor Darius II, the child of Achashverosh (Xerxes) and Esther, gave the Jews permission to rebuild the Second Temple. As a token of indebtedness (or at the insistence of the emperor), the Jews placed a carving of the city of Shushan, the capital of the Persian Empire, above the gateway.

Engraved onto the wall outside the Shushan Gate were two markings indicating the length of a cubit. One marking was to the right of the gateway, one to the left. The marking on the wall to the right was half a “fingers’ width” (etzbah) smaller than a true cubit. The marking on the left wall was a full “fingers’ width” larger than a true cubit. Workers, who were paid in lengths of wood, were paid according to the smaller marker. Workers hired to cut a certain length of wood would measure it according to the larger marking. Whoever pledged a length of inexpensive material to the Temple would measure it according to the larger marking, while those who pledged a length of expensive material, such as a precious metal, would use the smaller marker.