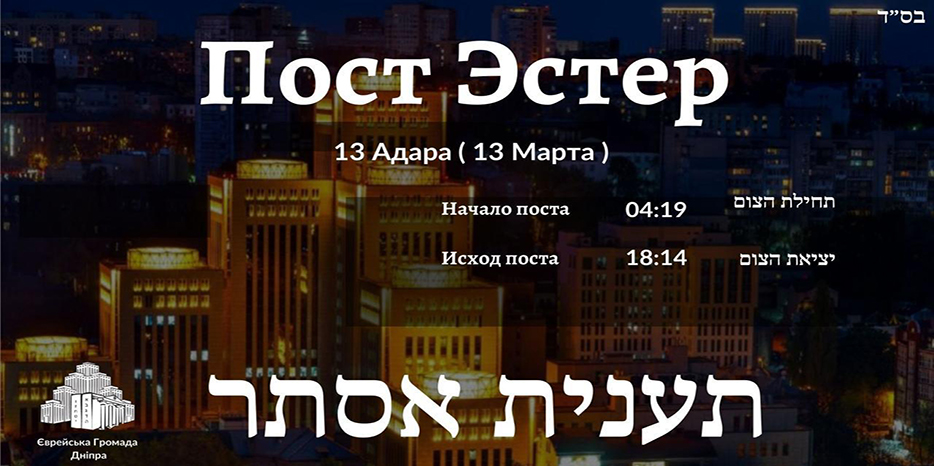

This year, the Fast of Esther (Taanit Esther) will be held on Thursday, March 13.

As is known, the day of fasting, called the “Fast of Esther”, was introduced in honor of the three-day fast declared by Queen Esther during the time of King Ahasuerus (Ahasuerus), when the events described in Megillat Esther unfolded.

Fast time (for Dnepr): March 13, from 04:19 am to 6:14 pm.

The famous code of Jewish practical laws, Kitzur Shulchan Arukh (in chapter 141 – “The Laws of Reading the Megillah”), speaks of this custom as follows:

“In the days of Mordechai and Esther, the Jews gathered together on the thirteenth of the month of Adar to defend their lives and take revenge on their enemies, and they had to ask for mercy from God, blessed be His name, so that He would help them. And as we know, the Jews, when they had to fight, fasted so that God would help them. And also our teacher Moshe, peace be upon him, fasted on the day when the Jews fought with the Amalekites.

And if so, then, of course, in the days of Mordechai and Esther, the Jews fasted on the thirteenth of Adar; and therefore all the Jews took upon themselves the obligation to observe a public fast on this day, which they called “the Fast of Esther,” to remind themselves that the Creator, blessed be His name, sees and hears the prayer of each one in the hour of his distress, if he fasts and returns to the service of G-d with all his heart, as our fathers did in those days.

However, this fast is not as obligatory as the four public fasts mentioned in Scripture (see chapter 121); and therefore one may be permitted not to fast on this day for those who need to, such as pregnant and nursing women, or even someone whose eyes hurt a little – if they suffer greatly from fasting, they may not fast. And the same applies to a woman in labor during the first thirty days after giving birth (A woman in labor should not fast, even if she is not suffering. Our sages argue about pregnant and nursing women who do not suffer from fasting, and everything depends on local custom).

And also, a young husband should not fast for all seven days of his wedding feast. And all of the above will have to “pay off” the missed fast later.

But ordinary healthy people should not separate themselves from the community (and neglect the public fast). Even if a person is on the road and fasting is difficult for him, he is nevertheless obliged to fast.

Much has been written about the meaning and symbolism of Esther’s fast. Here is what the magazine “Lechaim” wrote about it in the article by Yevgeny Levin “Fasting on the Eve of the Holiday”.

“Some believe that Jews fast on this day because it was at this time that Mordechai and Esther declared a fast in the Persian capital Shushan. This, however, is not true. According to the Talmud, Esther fasted from the 13th to the 15th of Nisan, that is, during the holiday of Passover (Babylonian Talmud, Megillah, 15a). Therefore, fasting on the same day as the Persian Jews during the time of Ahasuerus is simply impossible from the point of view of Halacha.

The first reference in Jewish classical literature to the custom of fasting on the eve of Purim appears in the tractate Sofrim (one of the so-called “small tractates” of the Talmud). According to the anonymous author, on the eve of Purim, the sages of the Land of Israel observed a three-day fast – in memory of Esther, who prayed for three days in a row before going to King Ahasuerus (Esther, 4:15). True, unlike the queen, they did not fast for three days in a row, but three daytime fasts, that is, only during daylight hours – since spending 72 hours in a hot climate without food and drink is dangerous to health or even life (Sofrim, 21:1).

Already in the era of the Geons, the three-day fast was replaced by a one-day fast. However, by this time, not only the sages but all other Jews fasted.

In Jewish literature, there are two explanations for why we fast on the 13th of Adar. According to Rambam, this fast was established in memory of the three-day fast of Mordechai and Esther on the eve of the queen’s visit to Ahasuerus: “The entire Jewish people adhere to the custom of fasting on the 13th of Adar, in memory of the fast in the time of Haman, as it is written: ‘So that they may observe these days of Purim in their proper time, which Mordechai and Queen Esther ordained for them, and as they themselves appointed them for themselves and for their children, days of fasting and weeping’ (Esther, 9:31)” (Mishneh Torah, Laws of the Fast, 5:5).

Rambam’s logic in this case is quite clear. The Book of Esther literally says: not “on the days of the fast,” but “on the days of fasts” (tzomot). Consequently, Rambam reasoned, we are talking not about a one-day fast, but about a multi-day fast. And the only multi-day fast directly mentioned in the Book of Esther is fasts 14-16 Nisan.

Another explanation was offered by the famous Spanish rabbi Abudargam-David ben Yosef (late 14th century, Spain, Seville). In his opinion, the fast on the eve of Purim could not have been established in memory of the fast of Queen Esther – because, firstly, unlike her, we fast only one day, not three days, and secondly, that fast, as already mentioned, was in the month of Nisan, during the holiday of Passover. Consequently, Abudargam-David reasoned, the fast of 13 Adar must have a different origin: “This fast was established in accordance with the following words of Scripture: “And the Jews who were in Shushan gathered on the thirteenth day of the “month of Adar” (Esther, 9:18).” “Gathered” – for a joint fast.”

The idea of fasting on the eve of a battle may seem strange. However, it should be remembered that, according to the Book of Esther, Haman, the main enemy of the Jews, was a descendant of the last Amalekite king, Agag (Esther 3:1). And according to Jewish tradition, during the first war with the Amalekites, which occurred shortly after the Exodus (when the Amalekites attacked the Jews without cause), Moses, Yehoshua and other Jewish leaders also fasted – in order to emphasize that they were relying not so much on the force of arms, but on help from above (see, for example, Rashi on Shemot 17:8).

There are many objections to this explanation in Jewish literature. The main one is that the fast of 13 Adar is not mentioned in the Book of Esther, so the assumption that the Jews fasted on this day is nothing more than a guess. However, this is the reasoning that was included in the Kitzur Shulchan Aruch: “In the days of Mordechai and Esther, the Jews gathered together on the thirteenth of the month of Adar to defend their lives and take revenge on their enemies, and they had to ask for mercy from the Most Holy One, blessed be His name, that He would help them. And as we know, the Jews, when they had to fight, fasted so that the Almighty would help them. And also our teacher Moshe, peace be upon him, fasted on the day when the Jews fought with the Amalekites. And if this is so, then, of course, the Jews fasted on the thirteenth of Adar in the days of Mordechai and Esther; and therefore all the Jews took upon themselves the obligation to observe a public fast on that day” (Kitzur Shulchan Arukh, 141:1).

The explanation offered by Abudarham-David contains a very important lesson. Queen Esther fasted at a time when Haman enjoyed unlimited influence in the state, and it seemed that the Jews had no hope of salvation. In such a situation, it is completely natural for a person to turn to the Almighty for help. However, on 13 Adar, the situation was fundamentally different. Haman had already been executed, Mordechai had become the first minister, the king had ordered “the satraps, chiefs and governors of the regions from India to Ethiopia, one hundred and twenty-seven regions” not to interfere with the Jews in dealing with their enemies, many non-Jews “were seized with fear of the Jews.” It would seem that victory was assured. However, Abu Dargam-David reminds us: even in such a favorable situation, a Jew should not rely only on himself – he should ask the Almighty for help and intercession. (In parentheses, we note that this can be useful not only from a religious but also from a psychological point of view, since it will allow one to get rid of excessive self-confidence, which has more than once led to defeat).

A few words about the laws and customs of Taanit Esther, the Fast of Esther. Since this fast is not mentioned in Scripture, its laws are much more lenient than those of other mourning days. In particular, pregnant and nursing women, the sick, and even those who find it difficult to fast due to hard work are exempt from it (Kitzur Shulchan Aruch, 141:2).

In medieval Provence and Germany, many Jews complained that they had difficulty enduring Taanit Esther. To “make life easier for them,” local rabbis (respectively Raavad and Rabbi Moshe Isserlin) allowed the Megillah to be read before dark. This decision proved unexpectedly relevant in the 20th century, when in 1947 the British imposed a curfew in Jerusalem, threatening to shoot anyone who left their home after dark. Remembering the medieval precedent, Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, who was asked what to do, allowed the Megillah to be read before dark.

Usually, if the fast falls on Saturday, it is postponed to the following day. However, with Taanit Esther this is impossible, since 14 Adar is the holiday of Purim. Therefore, if 13 Adar falls on Saturday, then since it is not possible to fast on this day, the fast is postponed to the previous Thursday, 11 Adar.

Many communities have a custom of giving a special tzedakah (donation) on the Fast of Esther – three coins worth half the local currency. This custom is reminiscent of the half-shekel – a special “tax” in favor of the Temple, which was collected starting from the new moon of Adar. The local rabbi should be consulted about how to behave correctly in a case where half a currency is insignificant.

Despite the fact that Taanit Esther is a day of fasting, many people come to the synagogue in festive, Shabbat clothes already during the mincha prayer. This custom is easy to explain: many, having come to the mincha, remain in the synagogue until the beginning of the holiday of Purim and, naturally, want to celebrate it in a solemn manner.

And in conclusion, about one more event that took place on the 13th of Adar. According to Sefer Taanit, it was on this day that Judah Maccabi achieved one of his most resounding victories – over the army of the Syrian commander Nicanor. Despite the overwhelming numerical superiority of the Greeks – 20 thousand against 6 thousand, the Jews “killed more than nine thousand of the enemy, and left an even greater part of Nicanor’s army wounded and maimed, and forced everyone to flee (II Maccabees, 8:24). Therefore, in the era of the Second Temple, 13 Adar was considered one of the days when public fasting was not appointed.

After all the political achievements of the Hasmoneans were lost, the reason to consider 13 Adar a solemn day also disappeared. However, in the future, this day will again become a day of joy and happiness. As Rambam writes, “All fasts will be abolished on the Days of Mashiach, and they will become days of joy and happiness” (Mishneh Torah, Laws of the Fast, 5:19). True, in this case, Rambam is referring to the fasts mentioned in Scripture – 10 Tevet, 17 Tammuz, 9 Av, 3 Tishrei. However, who knows – maybe this law will also apply to Taanit Esther.”

There are other opinions on the meaning and spiritual significance of this fast. We offer our readers an essay by Rabbi Uri Kalyuzhny on this topic:

“When they talk about fasting, many (like me) associate it with people sitting on the ground in sorrowful poses, crying and wailing. This feeling, of course, is inspired by famous paintings dedicated to the 9th of Av – the day when we all really mourn the destroyed Temple, galut and, at the same time, all the other troubles.

That is why every year, when Taanit (Fast) Esther approaches, I feel a certain bewilderment: “What is there to mourn about?” It seems that the story of Purim ended well, and, in general, as we know, the Sages said that with the onset of the month of Adar, one must fill the time with joy. So what is the point of crying and prayers? Let’s try to figure it out.

Taanit Esther is very different from other Jewish fasts. It is not mentioned explicitly in the Talmud at all. Only the day of the 13th of Adar is for some reason called “the day of the gathering of all.” And much later commentators explain that in the year when the events of the Esther scroll took place, on the 13th of Adar, that very decisive day when the Jews gathered and destroyed their enemies, was declared a day of fasting and all who could not go out with ordinary weapons gathered in the synagogue and turned to the traditional Jewish weapon – prayer. And the Almighty helped – we won. And for some reason, from that year onwards, the custom of fasting and prayer on the day of the 13th of Adar arose.

It seems that the defining feature of this day is that “everyone gathers,” as it is written in the Talmud, and the fast is only a mechanism that gathers people together.

I have witnessed this myself – in the company where I work, there are many religious people. On normal days, everyone prays at different times, in several places. Only on the day of the fast, because of the reading of the Torah, everyone gathers in one place. And on the previous fast – the 10th of Tevet – the minyan of the evening prayer numbered several hundred people.

However, we are still far from fully understanding. For example, why is this fast called the Fast of Esther? The chronology of the events of the Scroll of Esther is approximately as follows:

At the beginning of the month of Nissan, Haman received permission to destroy the Jews. He immediately cast lots, and it fell to him that this event should be scheduled for almost a year later, on the 13th of Adar. Secret letters were immediately sent throughout the country about the preparation of a “pogrom with state support.”

The Jews learned of this secret almost immediately, and already on the eve of the holiday of Passover, Mordechai came to Queen Esther and demanded that she intercede for his people. Esther agreed (at the risk of her life), but demanded that “all the Jews be gathered” and a three-day fast be declared. This fast fell on the first three days of Passover. Then, as is known, very interesting events took place and, as a result, 11 months later, instead of a pogrom of the Jews, there was a brilliant defeat of their enemies.

However, despite the fact that the dates of the fast declared by Esther and the fast we are celebrating do not coincide, common features are beginning to emerge. This is how Haman began his accusation against the Jews: “There is one people here, scattered and disunited.” This is what Esther said to Mordechai: “Go and gather all the Jews.”

Our people have three main weapons: national unity, the Torah, and closeness to G-d. Unfortunately, when Jews are in galut, we have no closeness to the Almighty. They obviously did not know the Torah at that time either. When they lost their national unity, our eternal enemy, Haman, realized that his time had come. But, thank G-d, we managed to unite quickly. And then we were able to win. This experience – the need for unity – has remained with us in the form of Taanit Esther. This is the starting point for all the upcoming holidays. And on Purim itself – giving alms to the poor, sending holiday portions to neighbors and acquaintances, a meal for which good friends gather – all this is called to strengthen our unity.

Of course, we cannot stop there – we must strengthen the connection with the Torah, get closer to G-d – but we must begin with this.”