On the eve of Passover, 14 Nissan 4895 (1135) (according to other sources, 4898 (1138)) in the Spanish city of Córdoba, a son was born to the family of Rabbi Maimon ben Ovadia, renowned for his learning. Moshe was a gifted boy, and his father taught him Scripture, Talmud, and mathematics.

In the year Moshe turned thirteen, Córdoba was captured by the Almohads—fanatical Muslim tribes. The new conquerors gave the city’s inhabitants a choice: convert to Islam or leave Córdoba immediately. Most of Córdoba’s Jews went into exile, including Rabbi Maimon’s family. They wandered for ten years, finding no refuge. Despite these hardships, young Moshe continued to study diligently, inspiring those around him with his faith and courage.

Finally, Rabbi Maimon settled in the city of Fez in northern Morocco. Moshe was then twenty-five years old. This region was also under Almohad rule, and the Jews were facing great hardship. It was then that Rabbi Maimon wrote his famous address in Arabic, which he sent to all the Jewish communities in North Africa. In this letter, he urged Jews to remain faithful to Judaism despite any trials, to study the Torah, to observe the commandments, and to remember to pray three times a day.

Within a few years, life for the Jews in Fez became completely unbearable. The community leaders were executed for refusing to convert to Islam. Rabbi Maimon’s life also hung in the balance, but he was saved by a friend, a local Arab poet. On a dark night in the spring of 1165, Rabbi Maimon and his family boarded a ship bound for the Land of Israel.

After a long and dangerous voyage, a few days before the holiday of Shavuot, they arrived at the port of Acre. The Jews of Acre, having heard of the great Torah scholar, greeted him with love and honor. But Rabbi Maimon’s family could not settle in Acre either, and after visiting the holy tombs of Jerusalem and Hebron, they departed for Egypt, known in those days as the “land of enlightenment and freedom.” They initially lived in Alexandria, but later settled in Fostat, the site of what is now the Old City of Cairo. There, Rabbi Maimon returned his soul to the Ashem.

Rabbi Moshe, who became known as Rambam (from the initials of the words “Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon”), continued his studies with unrelenting diligence. His younger brother, David, a successful gemstone merchant, provided for the entire family. But one day, news arrived that David had perished in a shipwreck in the Indian Ocean. Rambam suffered the death of his brother so severely that he became seriously ill, and it took a full year for him to recover.

He now faced the responsibility of supporting his family, as well as his brother’s young widow and her young daughter. Unwilling to profit from his knowledge of Torah, Rambam declined offers of rabbinical office. In his youth, he had studied science and medicine and now decided to become a physician.

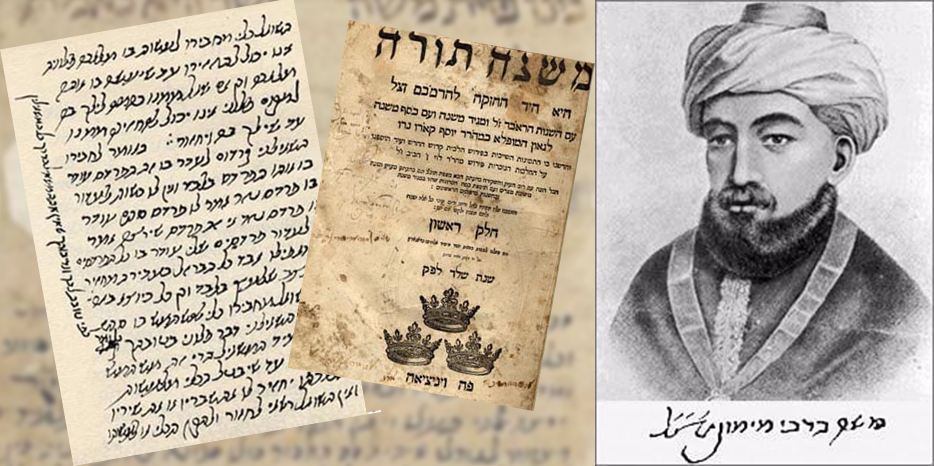

During his wanderings, exposed to dangers at sea and on land, Rambam not only constantly studied Torah and Talmud but also wrote commentaries on the Mishnah—the foundational collection of teachings of the Oral Torah, compiled by 190 CE by Rambam’s ancestor, Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, known as “Rabbenu Akadosh”—”our holy rabbi.” In 1168, at the age of 33, Rambam completed his work, which he wrote in Arabic, as Arabic was the spoken language of Eastern Jews.

His commentary on the Mishnah became widely known. Questions on Jewish law began to pour in to Rambam from even the most remote communities, and his opinions gained considerable weight. He was especially warmly received by the Jews of Yemen, to whom he sent “Igeret Teiman” (“Epistle to Yemen”) – a lengthy letter of sympathy and support at a time when all Jewish life there was threatened with extinction due to severe persecution.

It is simply incredible how much Rambam accomplished in a single day! He had to manage community affairs, devoted a full day to his medical practice, devoted several hours daily to studying Torah and Talmud, and also conducted extensive correspondence. And yet, in 1180, he completed his second major work, “Mishneh Torah” (“Repetition of the Torah”), also known as “Yad Achazaka” (“Strong Hand”). The letters of the word “yad”—yud and dalet—also represent the number 14. The Mishneh Torah is a vast, 14-book collection of laws, systematized based on the entire Talmud, written in simple and clear Hebrew in the style of the Mishnah, understandable to all Jews. Rambam divided these 14 books into chapters, each consisting of individual “halakhot” (laws), so that even someone unversed in the complexities of Talmudic analysis and the Aramaic language in which most of the Talmud is written could understand what the Torah prescribed, permitted, and prohibited in any given situation.

Around 1185, Rambam became the physician to the Egyptian vizier, and some time later, to Sultan Al-Aziz Uthman himself, the son of the famous Saladin. Now, people began to seek his medical help, even simply All the Egyptian nobility sought his advice. However, Rambam also found time to treat the poor free of charge, maintain extensive correspondence with Jewish communities in many countries, and continue to write works on medicine, astronomy, and philosophy. And all this despite his poor health and frequent illnesses.

In 1190, Rambam completed his famous philosophical work, Moreh Nevukhim (Guidance for the Perplexed). This book, written in Arabic, became widely known among both Jews and non-Jews.

In the last twenty years of his life, Rambam was the recognized leader (“nagid”) of Egyptian Jews, winning universal adoration. On the 20th of Tevet, 4965 (1204), he returned his holy soul to the Creator. His body was transported to the Land of Israel and he was buried in Tiberias. His tombstone bears the inscription: “From Moses to Moses there was no one like Moses.” In other words, his contemporaries believed that Rambam’s greatness was comparable to Moses himself, who received the Torah from the Almighty on Mount Sinai.