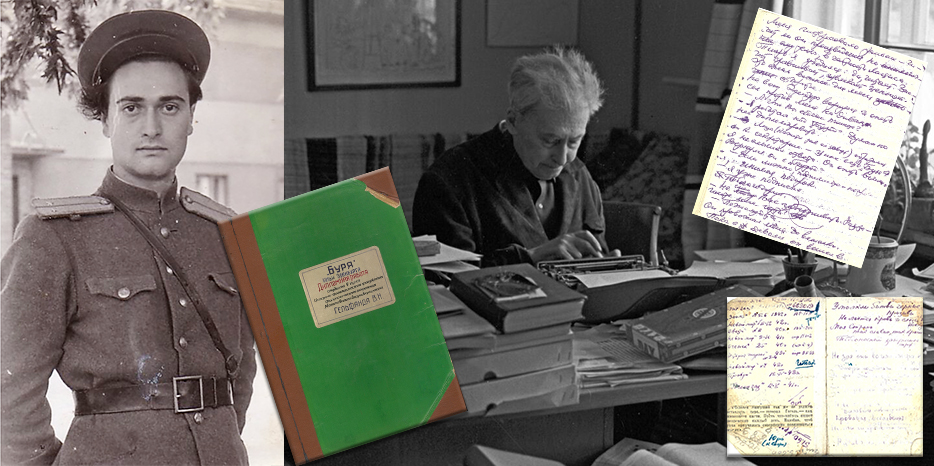

The Museum “The Memory of the Jewish People and the Holocaust in Ukraine” has published excerpts from the diary of Vladimir Gelfand, our fellow countryman, a famous teacher who kept a diary from his youth throughout his life and who is one of the outstanding examples of the diary of an “ordinary man” from World War II to the “era of stagnation”.

The diary for the period from 1941 to 1946 was published by his younger son Vitaly Gelfand and published in German, Swedish and Russian and its publication was an important event, however, the post-war diaries of Vladimir Gelfand have not yet been published.

The Museum of Jewish Memory and the Holocaust in Ukraine houses the largest archive of Vladimir Gelfand, including his post-war diaries, which were donated by his youngest son Vitaly Gelfand, now living in Germany and one of the most active organizers and participants in the movement in support of Ukraine.

The Jewish Museum of the Dnieper reported that for the first time a diary fragment from the period of 1951 has been presented to the general public. This first publication is accompanied by an introductory article by the Museum’s Deputy Director, candidate of historical sciences, Dr. Yegor Vradiy, which we republish with the kind permission of the author.

“Volodymyr Gelfand, like many of his peers who spent their childhood and youth in the 1920s and 1930s, was fascinated by the world of words. The digital era was still more than seven decades away. The prospects of mandrivoks beyond the borders of the Radian Union were as marginal as the poloty to other planets of the Galaxy. The book remained the only way to open the world and, in part, gave some hope for self-expression. One can only suppose what motivated the boy from the banks of the Dnieper to compose the first youthful lyrics. In this age, poetic endeavors are an integral part of many people’s lives, just like the first dreams, dreams of a heroic future and achievements in life.

As a schoolboy, Volodymyr attended various literary events that took place in the large in size and number of residents, but provincial in character pre-war Dnipropetrovsk. He occasionally ventured to make his own speeches and took both positive comments and critical remarks about his own creations with youthful acuity.

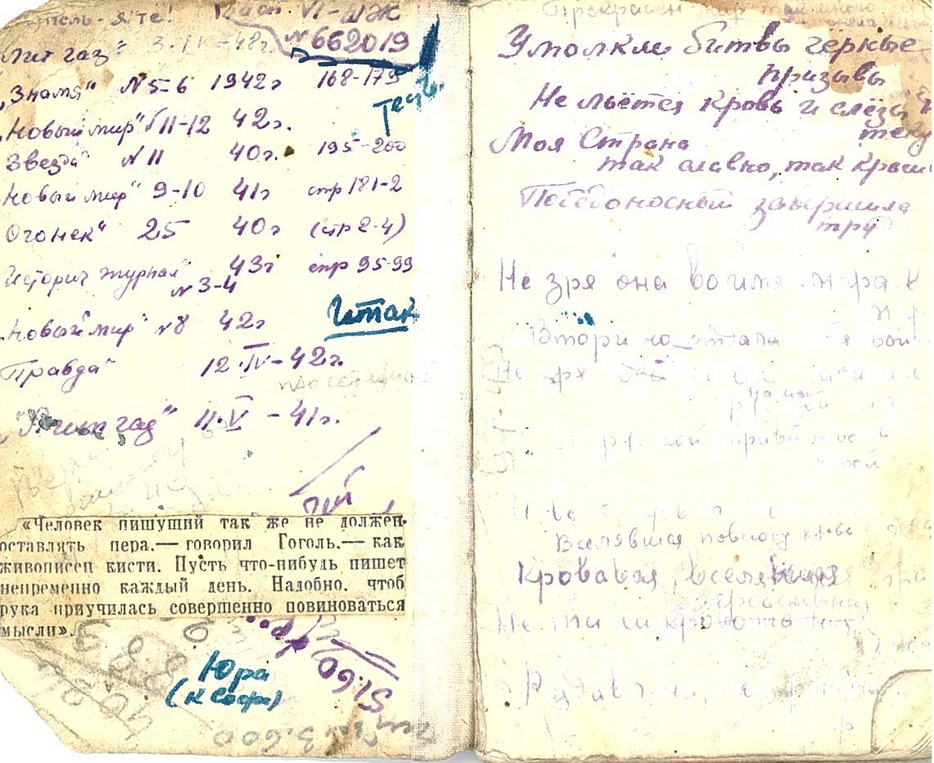

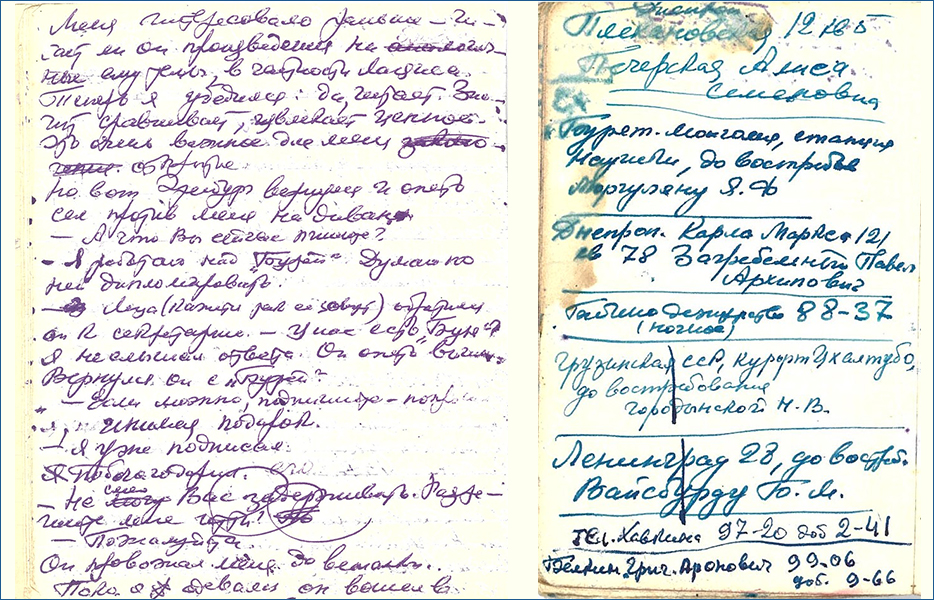

We learn about all this from his diary entries, and the diary itself (dozens of school ashes, notebooks, and separate books) turned out to be for a young boy, and later a grown-up man, both an original confidant and a magnum opus, which he wrote all his life.

The pages of the diaries contain all human experiences, achievements and losses. It’s like everyone else’s. However, the body of human history was hardship – the beginning of the German-Radian War, abandonment of the native town and evacuation to the unknown, mobilization to the Black Army and terrible trials of the war until its completion. However, even for such, often inhuman circumstances, the dreams of literary creativity and fame did not destroy the young man.

After the end of the war and postponed demobilization in 1947. Volodymyr Gelfand entered the Philology Department of the History and Philology Faculty of the Dnipropetrovsk State University. The end of the 1940s. The late 1940s is an extremely interesting period, because at that time a generation of 1941 graduates, many of whom, like Volodymyr, were burned by the war and the experience of survival, by the emotions of victory and the loss of close and fighting comrades.

In 1946 Oles Gonchar graduated from the university, and he entered the Ukrainian literature with the first part of his frontline trilogy “Praporonosci”. At the beginning of January 1948. V. Gelfand, describing the meeting of the university literary research and study group, gives in his journal a description of the reaction of the teacher to the news about the awarding of the Stalin’s Prize to O. Gonchar. Gonchar was awarded the Stalin’s Prize (II stage) for the famous “Praporonositsy”: “And Gonchar is our student, he received 50 thousand. He’s glad that he escaped from here. But he loves the university so much…”. Volodymyr was quite critical of the reaction of the teacher, believing that she was trying to bask in the glory of a talented graduate. However, it is entirely possible that he was caught by the materialistic approach to evaluating the literary work of another Togorich laureate, Illi Ehrenburg, who won the prize for his novel “The Tempest”: “Ehrenburg won 100 thousand…”.

For Volodymyr Gelfand, Illia Ehrenburg is not just a favorite author. He is a kind of literary deity with whom he was lucky enough to live at the same time, and at the same time an unattainable ideal. From the pages of the diary we can see how often Volodymyr often evaluates the works of other contemporary writers through the prism of comparison with the work of I. Ehrenburg.

Literary readings and discussions were part of the student’s life at that time. By the way, at this very time another gifted young man with no less dramatic share of the war period – Pavlo Zagrebelnyi – is a student of the faculty, but a year older. A year younger than V. Gelfand, he, nevertheless, entered the university earlier. It can be assumed that they knew each other and had repeated contacts. This assumption is supported by the address notes in the notebook of V. Gelfand. Gelfand, dated at the beginning of 1948: “Dneprop. Karla Marxa, 121, kv. 78. Zagrebelny Pavel Arkhipovich”.

No less interesting is a newspaper article pasted on the first page of the same notebook – a quote by Mikoly Gogol: “A person who writes should not polish his pen as much as a painter does a penzl. Let her write something, every day without fail. It is necessary that the hand be accustomed to absolutely follow the thought. What is this, if not a motivational devise for a young person so eager for literary recognition?

In 1949. In 1949, Gelfand married Berti Koyfman, a girl he had known since before the war and kept in touch with throughout the war, and transferred to the Philology Department of the Molotov State University.

Already here he, a student of the Russian philology department, looks at I. Ehrenburg’s works not only as a reader, but also chooses his works as an object for his student literary studies. The thesis is devoted to the analysis of the novel “The Tempest”. Working on it, V. Gelfand receives a permit to be assigned to the Moscow State University to collect materials and work in libraries. However, looking ahead, we can say that it was not the sole purpose of the trip. Somewhere deep in his soul Volodymyr was hoping to meet his literary idol. Moreover, there was a wonderful occasion – the 60th anniversary of the writer.

In preparation for it, V. Gelfand unsuccessfully tried to propose his articles on Yerenburg’s life, addressing the editorial offices of both central Radian newspapers and regional newspapers (including those in Dnipropetrovsk).

However, during the detachment he dares to make a desperate attempt to visit I. Ehrenburg’s apartment in Moscow. We could not find out how the ambitious student managed to find the address of the living classic of the Radyansk period. However, the fact remains that the short meeting took place on July 6, 1951.

It is a pity that my share was not as good before V. Gelfand. Gelfand as it was on this day at the beginning of July. He was not able to fully realize his desire for literature. Significantly due to life circumstances. In 1955 he returned to Dnipropetrovsk, where he lived the next 28 years. He worked as a teacher of Russian language and literature, and later of history and social studies. More than once he and his family became the objects of inverted anti-familial images and even persecution. In the 1960s-1970s. V. Gelfand published drawings in Russian and Ukrainian in the local press. However, he failed to create something great and integral, which he had dreamed of since his childhood.

Only thirty-five years after his death, thanks to the efforts of V. Gelfand’s son Vitaly, the first edition of his father’s military journals was published. Vitaly Gelfand’s son, Vitaly, published the first edition of his father’s military diaries. They continue to remain one of the most trustworthy accounts of “ordinary” people about the fear of war.

On Volodymyr Gelfand’s birthday, we would like to offer our readers a fragment of a diary entry about the meeting with I. Ehrenburg, which meant so much to a 28-year-old young man, full of dreams and plans for the future. This fragment is published for the first time.

Єгор Врадій”.

You can read the published excerpt from Vladimir Gelfand’s diary on the website of the Museum “The Memory of the Jewish People and the Holocaust in Ukraine” – https://jmhum.org/uk/founds/2069-mr-ya-buti-pis-mennikom.