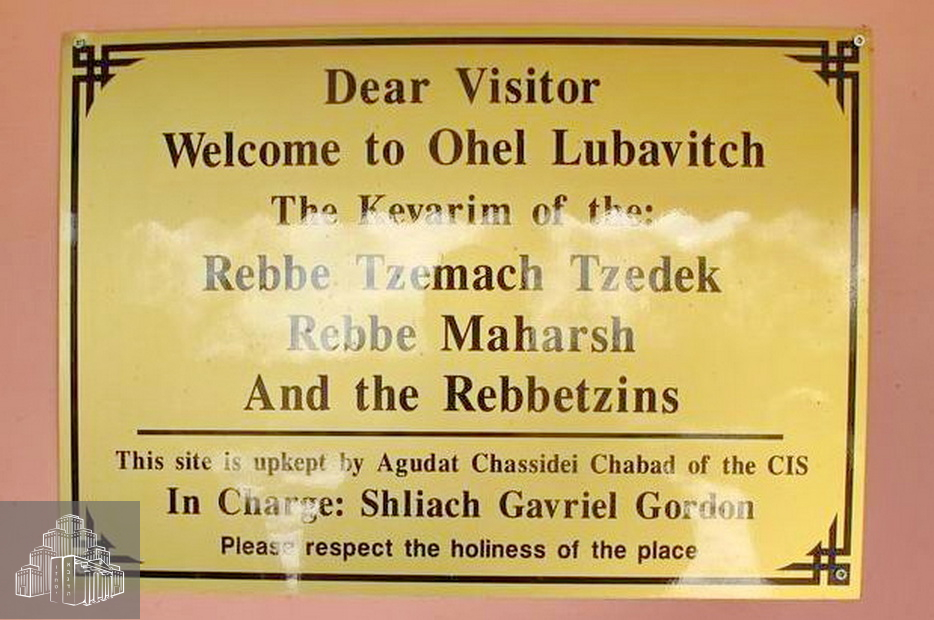

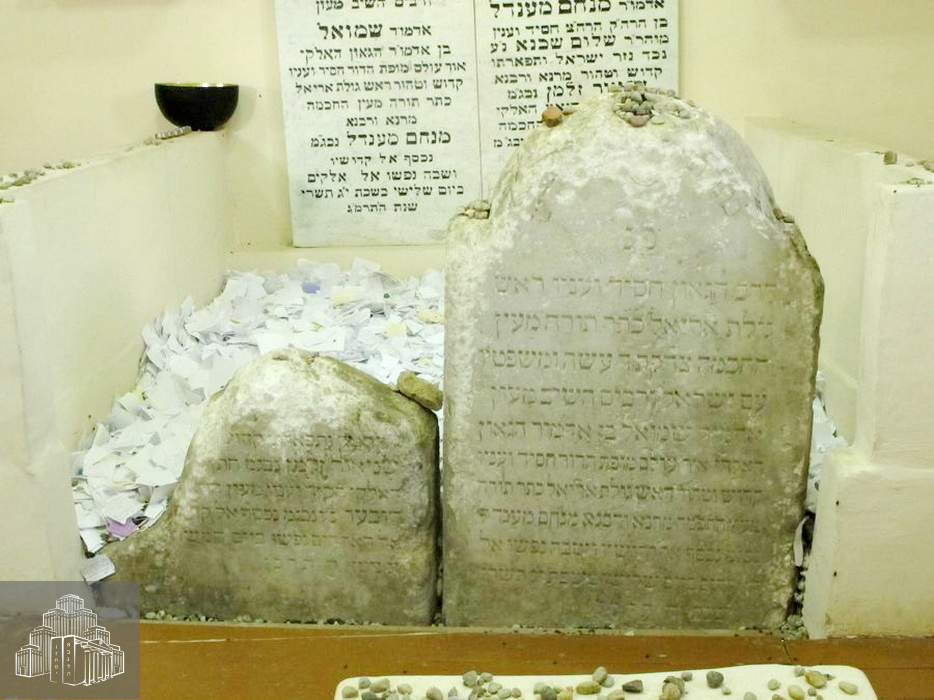

Today, with the coming 2nd of Iyar, we mark the 191st anniversary of the birth of the fourth leader of the Lubavitch movement, Rabbi Shmuel, also known as the Rebbe Maharash. He was the seventh son of the third Chabad Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel, the Tzemach Tzedek.

The second of Iyar corresponds to the Omer count day of Tiferet sheb’Tiferet (“Beauty within Beauty”), since the Torah commands counting seven weeks from the end of the first day of Passover until the festival of Shavuot. Each week corresponds to one of the seven sefirot – divine attributes: the first is Chesed (Kindness), the second is Gevurah (Strength or Judgment), and the third is Tiferet (Beauty, Splendor). The seven days of each week represent combinations of the week’s sefira with the other six, with one day representing that sefira in its pure form. Thus, the third day of the third week is Tiferet sheb’Tiferet – the “Essence of Splendor”.

There is a story in Chabad history about the Rebbe Maharash’s birth. His father, the Tzemach Tzedek, purchased a plot of land in Lubavitch to build a large house – a Beit Midrash and yeshiva. This was shortly after a major fire had swept through the town. It is said that the town governor, Count Lubomirski, ordered his estate manager to supply all the timber needed for the construction from the governor’s own forest – free of charge.

The housewarming was scheduled for Shavuot, but the Rebbe’s wife, Rebbetzin Chaya Mushka, wanted to give birth in the new home. When her labor began, she went there. In the new house, which had not yet been used, Passover utensils were stored, including a wooden bench used for sifting flour for shmurah matzah. It was on this bench that straw was laid, and the Rebbetzin lay down.

The account goes as follows: “When the Tzemach Tzedek was informed, he hurried to the new house, entered the room, and stood there facing the wall throughout the labor. He instructed his sons – Rabbi Baruch Shalom, Rabbi Yehuda Leib, and Rabbi Chaim Schneur Zalman – to recite specific chapters of Tehillim (Psalms): 1, 2, 3, 4, 21, 22, 23, 24, 33, 47, 72, 86, 90, 91, 104, 112, and from 113 to the end of the book. He also ordered the midwives to immerse in a mikveh before delivering the child and instructed them to receive the newborn in a special piece of white linen that he had brought.”

The entry of the infant into the covenant of Avraham Avinu took place on the 9th of Iyar, and there is also a meaningful story about it:

“On the eighth day after the birth of his son, the Tzemach Tzedek instructed that the morning prayers begin earlier than usual. By 10 a.m., all the household members had already gathered in the synagogue, led by Chaim Avraham – the son of the Alter Rebbe.

When it was already 2 p.m. and the Tzemach Tzedek was still secluded in his ‘Holy Chamber’, those gathered began to worry. Rabbi Chaim Avraham said: ‘Apparently, he is occupied with guests more distinguished than us,’ and sighed. After another half hour, the Tzemach Tzedek emerged from his room. His holy face was radiant, and his eyes were red from weeping. In his hand was a red handkerchief. The Rebbe said the circumcision would take place today, paused briefly, and returned to his room.

Rabbi Chaim Avraham rose from his seat, walked to the window, rested his head on his hands, and became lost in thought. The sons of the Tzemach Tzedek discussed Torah and Chassidic ideas, while the tension among the guests increased. The Rebbetzin sent someone to ask her husband why the circumcision was delayed for so long, but Rabbi Chaim Avraham stopped the messenger.

After 3 p.m., the Tzemach Tzedek again came out of his room with a glowing face and told the guests to prepare their hearts, because the circumcision would indeed happen today. Then he returned once more to his room. At 4 p.m., he came out a third time and instructed that the afternoon prayer not be started yet, as the circumcision would soon take place. Shortly after, he emerged from his room again, went to the room of the mother to discuss the naming of the child, and instructed that the baby be prepared.

During the circumcision, the infant cried intensely. Then the Tzemach Tzedek took his left hand out from under the pillow that rests on the knees of the one holding the child, placed it on the baby’s head — and the baby stopped crying.”

During the meal, Rabbi Yehuda Leib, the second son of the Tzemach Tzedek, asked his father whom the child was named after.

“It seems no one in our family had such a name,” he said, adding, “Maybe after the prophet Shmuel?”

The Tzemach Tzedek replied: “After the water-carrier from Polotsk named Shmuel — for a sage is preferable to a prophet.”

Yehuda Veksler, in an article about the Rebbe Maharash, emphasizes:

“The circumcision — that is, the entrance into the covenant which the Almighty made with Avraham — took place during the week associated with the Sefirah of Netzach (the will to triumph). It fell on the day combining it with the Sefirah of Tiferet: the 9th of Iyar, Tiferet she-be-Netzach, ‘Beauty within the will to triumph.’ And these two Sefirot — Tiferet and Netzach — largely characterize the personality and mission of the Maharash himself.”

His father, the Tzemach Tzedek, indicated this. The first time was when he examined his seven-year-old son in front of his teacher. The boy answered so impressively that the teacher, unable to contain himself, asked the Rebbe: “So? What do you say?!”

The Tzemach Tzedek replied: “What’s there to be impressed by — if ‘Tiferet she-be-Tiferet’ is doing its job well?”

In the year 5603 (1843), several prominent rabbis and public figures came to Lubavitch to consult with the Tzemach Tzedek. Among them was Rabbi David Luria from Bykhov, who engaged in a Talmudic debate with nine-year-old Shmuel on a difficult passage — and the boy convinced him he was right. Upon hearing of this, the Tzemach Tzedek said: “It’s no wonder — his circumcision fell on Tiferet she-be-Netzach!”

The Tzemach Tzedek knew the lofty soul possessed by his youngest son. In fact, he used to refer to his sons by the dominant trait in each — “my Chassid,” “my scholar,” and so on. But about the Maharash he would say: “All of it — is in him.”

By the age of seven, the Maharash already knew the Chumash (Pentateuch), most of the Prophets and Writings, and was studying Talmud with commentaries. At that time, he also began listening to his father’s Chassidic discourses, the maamarim.

By the time of his Bar Mitzvah (following the custom of the Rebbe’s household, instituted by the Alter Rebbe), he already knew the Mishnah by heart. The Tzemach Tzedek personally taught him the Tanya, which the child, like his father, had memorized by the time of his Bar Mitzvah.

From early childhood, the Tzemach Tzedek paid close and constant attention to raising his youngest son — literally never taking his eyes off him. This was noticeable even in minor matters and amazed everyone. The older brothers of Shmuel — most of whom later became Rebbes themselves — understood better than anyone that their father was preparing their younger brother in a special way for a unique mission: not just to lead a group of Chassidim, but to become a spiritual leader of the people of Israel.

Even as a child, through his charm, he managed to win the affection of elder Chassidim. From them, he heard many stories about earlier times and began recording them as soon as he learned to write. (In this too, he followed the example of his father, who at the same age spent as much time as possible in the company of elder Chassidim, listening to their conversations.)

When Rebbe Shmuel was approaching his eighteenth year, the Tzemach Tzedek told his son that it was time to take the exam for receiving semicha — rabbinic ordination. The Maharash followed his father’s instruction and — on several occasions, at different times — received semicha from the leading rabbis of the time, including the brilliant Rabbi Yitzchak Aizik Epstein, the rabbi of Gomel, and the renowned Chassid and tzaddik Rabbi Hillel of Paritch. However, he kept his knowledge hidden and conducted himself with remarkable modesty. One incident in particular illustrates this.

From the age of twenty-one, by the instruction of the Tzemach Tzedek, the Maharash began engaging in communal affairs, often undertaking very difficult missions from his father — typically carried out discreetly.

Once, while passing through the town of Belz, the Maharash, dressed modestly like a merchant, entered the beit midrash of the famed Rabbi Sar Shalom, the founder of the Belz dynasty. The hall was full of Chassidim, and when the tzaddik (who was blind) entered, a path was cleared for him from the door to his seat. However, as soon as he stepped inside, Rabbi Sar Shalom paused and said he sensed a wonderful fragrance. Then he decisively made his way toward the Maharash, who stood quietly in a far corner. The Rebbe took him by the hand and said: “Young man, you can’t hide from me!” — and led him to his own place. One of the Chassidim tried to “correct the mistake,” saying: “Rebbe! But he’s just a simple merchant!”

“Indeed!” he replied. “He is a merchant: ‘For her [the Torah’s] acquisition is better than any merchandise.’”

“No one sees anything remarkable in him, and no one knows anything about him,” recalled one of the senior Chassidim, Rabbi Dan Tomarkin, “but once you begin speaking with him — there is not a single area of Torah he does not know thoroughly. He learns Torah quietly, for its own sake, and naturally fulfills the Mishnah’s words: ‘<…> They grant him royalty and authority <…> and reveal to him the secrets of the Torah <…> and it exalts him and elevates him above all other pursuits.’”

So it is no wonder that at the beginning of the year 5626, the final year of his life (that is, in the fall of 1865), the Tzemach Tzedek instructed the Maharash to begin publicly delivering maamarim — essentially, to act as Rebbe. Shortly before his passing, he wrote to the Chassidim: “Listen to him as you listened to me.”

To the Maharash himself, the Tzemach Tzedek left the following testament:

“…Be strong and courageous to write and to speak, and I grant you full permission. Fear no one, and the Almighty, blessed be His Name, will grant you success — both materially and spiritually: to learn and to teach, to observe and to fulfill.”

And he signed: “Your father, who cares for the welfare and benefit of our Chassidim.”

The entire life of Rebbe Maharash was filled with trials; to withstand them, he constantly had to awaken and renew within himself Netzach — the will to prevail.

At the age of thirteen, the Maharash was betrothed to the daughter of his older brother, Rabbi Chaim Schneur Zalman — the third son of the Tzemach Tzedek. Both the preparations for the wedding and the celebration itself were filled with a festive spirit. However, during the “seven days of feasting” following the wedding, the young bride fell seriously ill and passed away three months later. To console his son, the Tzemach Tzedek placed him in the room next to his own study, granted him permission to come in at any time, dedicated more time to learning with him, and showed him manuscripts he had never shared with anyone else. Two years later, in the summer of 5609 (1849), the Maharash married Rivka, the daughter of Rabbi Aharon Alexandrov of Shklov, and granddaughter (on her mother’s side) of the Mitteler Rebbe, Rabbi DovBer.

As previously mentioned, already during the Tzemach Tzedek’s lifetime, the Maharash began active involvement in public affairs. Under his father’s directives, he established personal contacts both in Russia — particularly within government circles — and in Western Europe, mainly among influential Jewish financiers and communal leaders. His first major success came in 1863, when — through his personal intervention in Kyiv and negotiations with the governor — he saved hundreds of Jewish families from being expelled from villages in Volhynia. In 1865, the Maharash traveled to St. Petersburg and succeeded in repealing a proposed set of new restrictions on Jews in Lithuania and Western Ukraine. Later, in 1869, he organized a permanent Jewish council in St. Petersburg to address communal concerns. In both 1870 and 1879, despite his deteriorating health, the Maharash exerted tremendous effort to quell emerging waves of anti-Jewish pogroms.

A staunch defender of the principles of Judaism, the Maharash often ignored the opinions and egos of the assimilated “urban elite” Jews — and thus incurred their fierce animosity. This was especially evident in 1880, when a state-sponsored wave of pogroms began to rise, and the Rebbe, urgently returning from abroad, arrived in St. Petersburg. He managed to gain support from high-ranking officials, but they advised that, for greater impact, the Minister of the Interior and the head of the Senate should be visited by a Jewish delegation made up of prominent financiers, wealthy individuals, and scholars — led by the famed philanthropist and patron of science and the arts, Baron Horace Ginzburg.

The Rebbe convened the proposed delegates for an emergency meeting and laid out a detailed plan of action. But Ginzburg responded indignantly:

“What are we, logs? To be moved around like pawns?! If we truly are prominent people, you must consult with us regularly — and if not, then you can manage this without us!”

The Maharash replied:

“It is written in the Megillah: ‘For if you remain silent at this time, relief and salvation will come to the Jews from another place, but you and your father’s house will perish.’ I have no doubt that ‘relief and salvation will come to the Jews’ — and if you do not want to be part of it, it will come ‘from another place.’ But then — ‘you and your father’s house will perish’!…”

And the Rebbe went to the Minister of the Interior by himself — accompanied only by two Chassidim.

The minister received the Rebbe warmly, but the Maharash openly reproached him for failing to fulfill his earlier promise to stop the pogroms, pointing out that such actions were drawing negative attention from abroad. The official admitted that he was well aware of the great power of foreign Jewish capitalists, but also noted that they held no sympathy for Russian Jews — and in fact, harbored outright disdain for Orthodox rabbis.

“You have no understanding of the psychology of Jews and of their brotherly love for one another,” replied the Rebbe. “I receive inquiries from influential capitalists abroad, asking how to respond to the disturbing reports about the situation of Jews in Russia and what can be done to protect their lives and property.”

“And what did you reply?” the minister asked irritably.

“I refrained from answering until I hear the response of the Russian government to my petitions.”

“You are threatening the Russian government with the intervention of foreign capitalists?!” the minister raised his voice.

“The minister must not take my words as a threat,” the Rebbe answered boldly, “but must regard them as a very serious fact. Because support will be extended even by non-Jewish capitalists — for such barbaric actions demand a strong response from all humanity!”

“So, you intend to incite a revolution in Russia with the help of foreign capital?!”

“That revolution will eventually be brought about by Russian statesmen themselves — with their bureaucracy and irresponsibility,” the Maharash replied fearlessly, and left.

When he returned to his hotel, he lost consciousness. A doctor, Professor Joseph Bertenson — who had sympathies for the Rebbe and had treated him during previous visits to Petersburg — was immediately summoned. Incidentally, it was Bertenson who had arranged the Rebbe’s meeting with the Minister of the Interior. The doctor examined the Rebbe, gave care instructions, and visited him several times. For nearly two days, the Maharash remained unconscious. When he regained consciousness, Professor Bertenson reproached him for completely neglecting his health.

“All my fathers,” the Maharash replied, “were willing to sacrifice themselves for the people of Israel, and I can do no less.”

Two weeks later, a favorable response was received from the minister, and the pogroms ceased — at least for a time.

But the Maharash did not only sacrifice himself for the Jewish people as a whole — he did so even for individual Jews. The Rebbe Rayatz told the story of how the Maharash once abruptly interrupted his treatment at a health resort and went to Paris for one reason only — to enter the gambling hall of the most luxurious hotel, approach a certain player, and quietly say to him in Hebrew: “Young man, non-Jewish wine deadens both the mind and the heart. Be a Jew!”

One of the Maharash’s attendants later recounted that he had never seen the Rebbe in such turmoil. And the person to whom the Rebbe spoke during the game was so deeply moved by the words that he sought out the Maharash at the hotel and asked to speak with him. They spoke privately for a long time. Then the young man left, and the Rebbe immediately departed Paris. Later, the Rebbe said that for generations, such a pure soul had not descended to this world, yet it had fallen captive to the forces of impurity. Shortly after the Maharash returned to Lubavitch, that young man came there as well — having completely changed his way of life and conduct.

There is a “rule of the Rebbe Maharash” — lechat’chila ariber (“go over from the outset”). The Maharash often said: “People usually say: if you can’t overcome an obstacle from below, try to climb over it from above. But I say: lechat’chila ariber — from the very beginning, overcome it from above.” This is exactly how he lived, and this is how he taught his chassidim — and all Jews — to live.