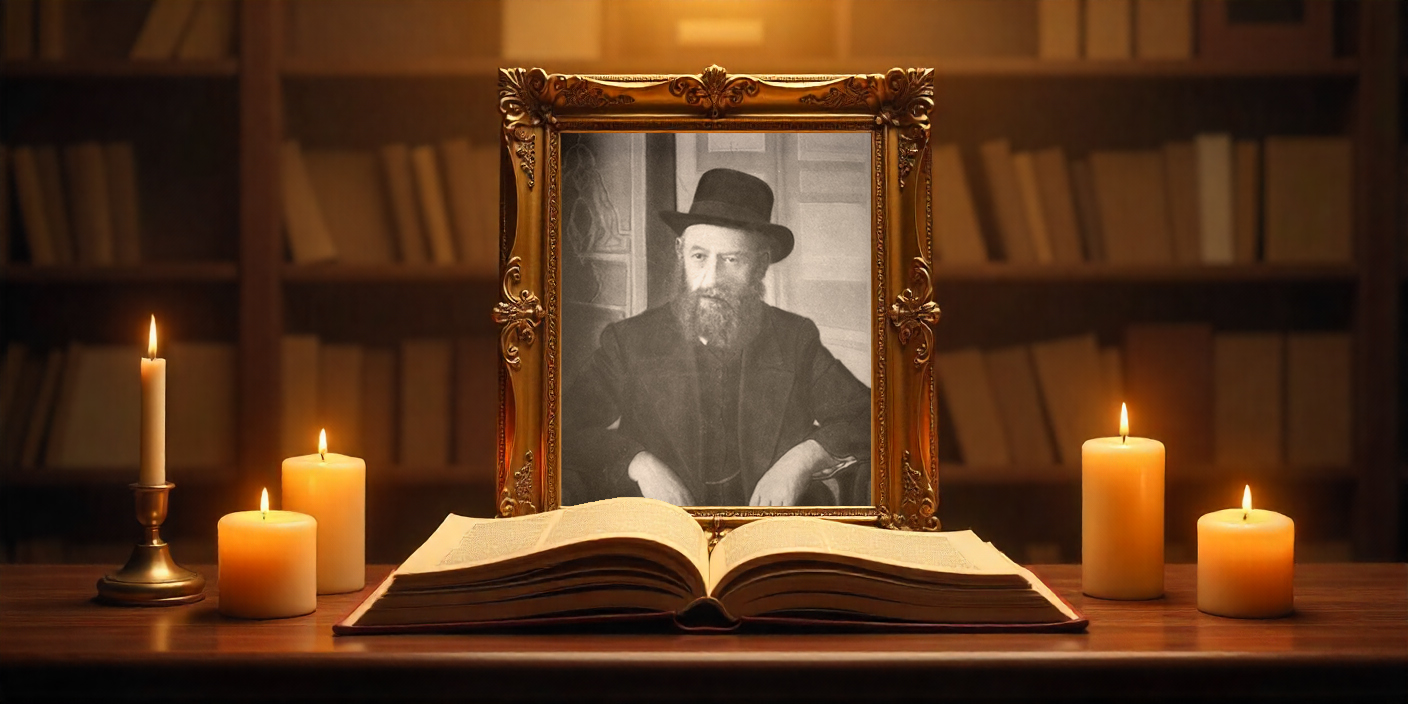

Today, 20 Cheshvan, marks the 165th anniversary of the birth of the Fifth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Sholom Dovber. He was born in the town of Lyubavichi (now a village on the Russian-Belarusian border) in the year 5621 (1860). His father was Rabbi Shmuel (the Maharash), the Fourth Lubavitcher Rebbe, and his mother was Rebbetzin Rivka.

The Rebbe Rashab led the Jewish people at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. He was the founder of the famous yeshiva “Tomchei Temimim,” waged an uncompromising struggle against assimilation and attempts to alienate Jews from their ancient religion, and zealously defended his people from the antisemitism of the Russian and later Soviet authorities. Along with many Jews of Belarus, he survived the ethnic cleansing of 1915, orchestrated by the Russian government, when Jews were forcibly resettled deep into the empire. Separated from his native Lyubavichi, which had been the capital of Chabad for 102 years, but surrounded by faithful chassidim, the Fifth Lubavitcher Rebbe moved the center of Lubavitch Chassidism to the city of Rostov-on-Don. It was in this city that he departed from the material world on 2 Nisan 5681 (1920).

A story about his birth, told to the world by his mother, the righteous Rebbetzin Rivka, has been preserved.

“On the 10th of Kislev 5620 (1859), my mother, Rebbetzin Chaya Sarah, my grandfather, the Mitteler Rebbe, and another chassid whom I did not know appeared to me in a dream. ‘Rivka, you and your husband must write a Torah scroll,’ my mother instructed me. ‘You will have a wonderful son. When you give him a name, do not forget about me,’ asked my grandfather. ‘And about me,’ added the chassid. ‘Rivka,’ my mother addressed me again, ‘do you hear what my father is saying?’

At that moment I woke up. The dream stayed in my head all day, but I did not tell my husband anything.

By that time, my mother-in-law, Rebbetzin Chaya Mushka, had already been in bed with a high fever for two or three days, and I was constantly by her side. At night, however, she felt better.

In the morning, after prayers, my father-in-law, the Tzemach Tzedek, came to visit the sick woman, and she said that she had had a dream that day.

‘It is said in the Talmud that a dream is a good sign for a sick person,’ the Rebbe responded. ‘There are two opinions regarding dreams. One says that dreams should be believed, and the other claims that dreams cannot be believed.’ Here he looked at me and added: ‘But if an instruction is received in a good dream, it should be carried out.’

When the Rebbe left, I pondered his words and decided to tell my husband about my dream. However, upon returning home, I found that our daughter Dvora-Leah had a sore throat and a fever. For three days I was busy treating her, and in these cares, I forgot about everything else.

On the night of the 19th of Kislev, my mother appeared to me in a dream again. She was accompanied by my grandfather and an elder of majestic appearance.

‘Rivka, you and your husband must write a Torah scroll,’ my mother told me. ‘And you will have a wonderful son,’ added my grandfather. ‘Amen! May it be His will!’ said the elder. ‘Zeide,’ my mother addressed him, ‘bless her.’

I understood that this was the Alter Rebbe. He blessed me, and my mother and grandfather answered ‘amen.’ I also answered ‘amen’ in a full voice and immediately woke up.

My husband had woken up before me but was still in the room. Hearing me say ‘Amen’ so loudly, he asked why I had done so. After washing my hands, I replied that I had had a dream and would come to him in an hour and tell him everything.

‘Good dream,’ said my husband when I told him about my nightly visions. ‘Why haven’t you told me about it until now? Such dreams are from a very high source!’

The Tzemach Tzedek, hearing about my dreams, asked me to describe whom I had seen the first time. When I told him everything, he informed me that the chassid I did not recognize was his father, Rabbi Sholom Shachna.

My husband decided that our Torah scroll would be written on parchment made from the skin of a cow slaughtered according to the requirements of Jewish law. Obtaining such parchment was very difficult, and five weeks passed before we managed to acquire at least a few sheets for the sofer to begin work.

The Tzemach Tzedek told my husband that the start of work on the scroll must be kept secret, it must be written in the Rebbe’s study, and only my husband’s brothers could be present. The writing of the scroll began on the 15th of Shevat. Writing a Torah scroll is slow, painstaking work requiring extreme attentiveness. My husband, knowing this, nevertheless asked the sofer not to delay the work because he wanted to complete it as quickly as possible.

In the month of Elul, the scroll was almost completely ready. My husband wanted to celebrate the completion of the writing of the scroll on the morning after Yom Kippur, on Thursday, and his father, the Tzemach Tzedek, agreed.

On Rosh Hashanah and during the Ten Days of Repentance, a rumor spread that the completion of the new scroll would take place on the day following Yom Kippur. Many of the chassidim who had come to the Rebbe for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur decided to stay another day to participate in the upcoming celebration.

The day after Yom Kippur, early in the morning, the Tzemach Tzedek called my husband to him and said: ‘Today you must organize a festive meal. I will also participate in it and deliver a maamar. But the completion of the writing of the scroll must be postponed.’ Why – the Rebbe did not explain.

A month later, on the 13th of Cheshvan, he again called my husband to him and said: ‘Tonight the sofer must come to my study. Tell your mother to come too. But we must not publicize the completion of the writing of the scroll.’

In those days, I was about to give birth and therefore hurried to finish the mantle I had decided to sew for the new Torah scroll. When I brought the mantle to the Rebbe’s study, he said loudly: ‘Mazel tov! May it be G-d’s will that the blessing of my father-in-law, the Mitteler Rebbe, and my grandfather, the Alter Rebbe, be fulfilled!’

A week after the Torah scroll was completed, on the 20th of Cheshvan, on Monday, at nine o’clock in the morning, I gave birth to a son…

In honor of the newborn’s circumcision, we held a large feast, attended by many guests from all the surrounding villages and towns. In the evening, on the Shabbat of the portion “Chayei Sarah,” a “ben zachar” farbrengen was held at our home. Another farbrengen was held after the morning prayer. The Rebbe was present both times. Both in the evening and during the day, he sat at the table for about an hour and delivered a maamar. It was evident that he was in great joy.

According to tradition, on the night before the circumcision (vacht nacht), dozens of guests, including my husband’s brothers, read Tehillim, sang nigunim, and studied the book of Zohar.

My mother-in-law was unwell, and her daughter, Dvora-Leah, was in the room with her. At three o’clock in the morning, the Rebbe called his assistant, Chaim-Dov. My mother-in-law, hearing this, sent Dvora-Leah to find out what was the matter. Returning, Dvora-Leah informed her mother that the circumcision would not take place the next day. The Rebbe had decided so and ordered the assistant to convey this to my husband.

My mother-in-law, upon learning this, was extremely upset and sent her daughter to the Rebbe with a request not to tell either my husband or me that the circumcision would not take place on time. I was still very weak after childbirth, and my mother-in-law protected me from all sorts of worries and anxieties.

The Rebbe replied that he was aware of the events and had good reasons why he had to inform his son that the day of the circumcision would have to be postponed. My mother-in-law again sent Dvora-Leah to him and asked that her request be treated with due respect, as she was the daughter of a Torah scholar.

‘What should I do?’ replied the Rebbe. ‘I really cannot refuse her, as the daughter of a scholar. But the matter is exactly as I said. Everything happens according to Divine Providence. The writing of the Torah scroll ended exactly when it was supposed to end. And the infant must also enter the covenant of our forefather Abraham on the day appointed for it.’

In the morning, on Monday, everything in the synagogue was ready for the circumcision. Candles were lit. During the prayer, “Tachanun” was not recited. After the prayer, the Rebbe entered, who was given the honor of being the sandak. The chair of the Prophet Elijah was brought to him. The infant was brought in, and my husband, who was himself a mohel, prepared to perform the commandment of circumcision. However, upon examining the child, he realized that the circumcision could not be performed now.

Other mohels also examined the newborn and agreed with my husband that the circumcision should be postponed for a few days.

The Rebbe remained in the synagogue, made a lechaim, and delivered a maamar. The farbrengen continued until the Mincha prayer. After the prayer, the Rebbe delivered another maamar.

Another month passed. Hanukkah arrived. On Monday, the second night of the holiday, the Rebbe called my husband and said:

‘Tomorrow you must perform the circumcision on your son. But without any celebration or unnecessary noise. Everything must take place in the room where I pray. Only your brothers and closest relatives may be present. No more than twenty people in total. Concerning the Second Tablets, which were given in silence, without thunder and fire, without a great revelation of Divine light, it is said: “They shall not depart from your mouth, nor from the mouth of your children, nor from the mouth of your children’s children,” said the Almighty, “from now and forever.”‘

The story of Rebbetzin Rivka is based on the text published on the website https://ru.chabad.org