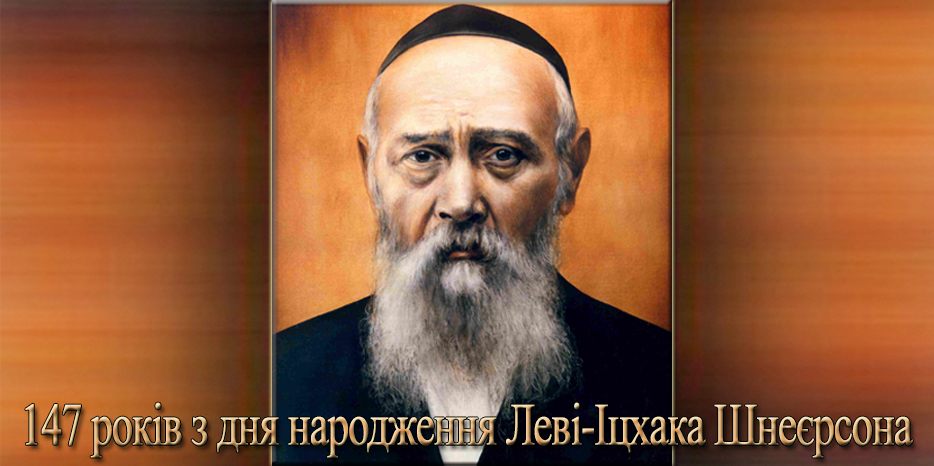

Today, on the third day of the Counting of the Omer, the 18th of Nissan, marks the 147th anniversary of the birth of the righteous Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson. From 1909 to 1939, he served as the Chief Rabbi of the city now known as Dnipro, which at the time was first called Yekaterinoslav and later Dnipropetrovsk. He was the father of the leader of our generation, the Seventh Lubavitcher Rebbe, Menachem Mendel Schneerson.

The entire life of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson stands as an example of unwavering dedication to his people, unbreakable spiritual strength, and a readiness to fight uncompromisingly for every Jew—for their right to faithfully observe the commandments and traditions. In addition to his recognized spiritual leadership, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson became renowned as one of the greatest religious thinkers of our time.

In Dnipro, the memory of this remarkable man is honored with reverence— a lyceum and a yeshiva bear his name, and hundreds of Jewish boys in our city are named after him. His short biography is published in the “Founders” section of our website: “Levi Yitzchak Zalmanovich Schneerson was born on the 18th of Nissan, 5638 (1878), in the village of Poddobryanka near Gomel. His lineage traces back to the third Lubavitcher Rebbe, the Tzemach Tzedek. Levi Yitzchak began studying Torah under Rabbi Yoel Haikin of Poddobryanka, his mother’s uncle. He quickly surpassed his teacher and continued studying the sacred texts on his own. Rebbe Rayatz wrote that ‘from a very young age, Levi Yitzchak displayed extraordinary abilities and diligence.’ He received rabbinical ordination (semicha) from two of the greatest authorities of the time: Rabbi Eliyahu Chaim Meisel of Lodz and Rabbi Chaim of Brisk.

In 1900, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak married Chana, the daughter of Rabbi Meir Shlomo Yanovsky. Their match was arranged by the Fifth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Sholom DovBer Schneerson. After the wedding, the young couple moved to Nikolaev, where Chana’s father served as a rabbi. In Nikolaev, on the 11th of Nissan, 5662 (April 18, 1902), Levi Yitzchak and Chana’s son, Menachem Mendel, was born. Later, two more sons were born into the family: DovBer and Yisrael Aryeh Leib.

In 1907, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak and his family moved to Yekaterinoslav. They settled on the second floor of building No. 20 on Zhelezna (now Myronova) Street. Later, from 1928 to 1934, they lived at No. 15 on the corner of Zhelezna and Upornaya (now Hlinky) Streets. Their final residence was on Kudashovskaya Street (now 16 Barykadna Street).

In 1909, at the age of 31, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak was invited to become the rabbi of the Yekaterinoslav community. The period of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak’s life in Yekaterinoslav was described by Mikhail Karshenbaum in “ShSh” No. 2, 1991: “His election was not smooth. The local intelligentsia opposed the young rabbi’s candidacy, wishing for a less orthodox individual to be appointed as the spiritual leader of the community. They turned to the most authoritative person in the city, engineer Sergey Pavlovich Paley, one of the leaders of the local Zionist organization, asking him to use his influence to prevent the election of a Chasid from the Schneerson dynasty. Paley said he didn’t like following anyone’s lead. He decided to meet the candidate himself and went to Rabbi Levi Yitzchak. They spoke for six hours, and after the conversation, Paley became one of the strongest supporters of the new rabbi.”

By 1925, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak’s authority had grown so much that he was offered the position of Chief Rabbi of Jerusalem. However, he remained in Yekaterinoslav. A distinctive feature of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak’s work was his organization of aid for the needy. During the Beilis trial, he helped create a fund to pay for lawyers. At the beginning of World War I, together with Rebbetzin Chana, he organized aid for refugees.

In Yekaterinoslav, besides his father, young Menachem Mendel had a teacher named Schneur-Zalman Vilenkin. In the mid-1920s, Menachem Mendel moved to Leningrad and, in 1927, left the USSR with the family of the Sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Yosef Yitzchak Schneerson. In 1929, he married the daughter of Rebbe Chaya-Mushka in Warsaw. In congratulating his son on his marriage, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak wrote: “From the deepest depths of my heart, I bless you, my son, my joy, on your marriage to Chaya-Mushka. May it be a good hour. And may the G-d of our holy forefathers, by whose merit we act and live, spread a veil of peace and prosperity over your home, so that it may stand unshakable. Enjoy happiness with your beloved wife in the simplest and deepest sense. May the merits of your common ancestor, Rebbe Tzemach Tzedek, and his wife, whose names match yours and your wife’s, always protect you. By following the path of the Torah and observing its commandments, may your life be filled with peace, tranquility, and every good thing that can be sent. May you be a pride and ornament of the Jewish people…

Your father, who is always with you, truly with you.”

The situation for Jews who observed the commandments of the Torah in the country was difficult. They could not work in enterprises operating on Shabbat. The government did not accommodate believers. Many families were in a catastrophic situation. Seeing this, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak organized a fund to support the needy members of his synagogue, which caused sharp irritation from the authorities.

A congress of rabbis from Ukraine was convened in Kharkov to make a statement favorable to the Bolsheviks, claiming that there was no religious discrimination in the USSR. Rabbi Levi Yitzchak refused to sign the document prepared by the organizers. Rabbi Levi Yitzchak did much for the religious Jews of the city. He managed to get an audience with M. I. Kalinin and obtained permission to personally supervise the kashrut of flour for baking matzah.

Using the formal statements of Soviet leaders about freedom of religion and human rights, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak resolutely defended the religious needs of Jewish communities. Even at that time, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak became famous as a righteous man and a great scholar of the Torah. Stories about him became legendary. For example, one goes like this: One late night, there was a knock at his door. A frightened woman stood at the threshold. “Rebbe, you must help us, my daughter is getting married. Can’t the new family begin without a Jewish wedding, without a chuppah?” At midnight, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak and his wife, Rebbetzin Chana, invited reliable people. They were still one short of a minyan—since a chuppah is typically not held without one (though it can be). In the same building, one floor above, lived a Jew who was the head of the house committee, and concurrently an NKVD informant assigned to Rabbi Levi Yitzchak. Rabbi Levi Yitzchak invited him to serve as the tenth man. The wedding was held without music, without a feast, with a tablecloth stretched over four corners as the chuppah. But does this hinder true Jewish joy and the great miracle of the union of two pure Jewish souls, which no regime or prohibition can prevent? The family began their life according to all the rules, against all odds. Who knows how many children, grandchildren, and even great-grandchildren of this couple now live beside us…

Early in the morning, while it was still dark, the guests began to leave. The happy bride and groom, together with the mother, departed – seven more days of celebration awaited them, which they would also secretly observe at home. Rabbi Levik returned to his daily responsibilities. But who said that organizing and conducting a Jewish wedding is not part of the rabbi’s everyday duties? This story would be incomplete without one particular detail, which is by no means secondary.

What happened to the head of the house committee, the “tenth” Jew? From that very day, or more precisely, from that night, he became a devoted disciple of Rabbi Levik. Soon after, he fully returned to Judaism and would often come to the aid of the Rebbe, interceding for him with the authorities. Unfortunately, his intercession did not always bring success. Rabbi Levi Yitzchak was eventually exiled to Kazakhstan, where he passed away.

In 1927, Menachem Mendel Schneerson permanently left Russia. He was never to meet his father again. The younger brother, Aryeh-Leib, lived in Leningrad for several years. In the early 1930s, he left for the Holy Land, where he passed away at a very young age (in 1952), and was buried in Safed’s old cemetery. Very little is known about the middle son of Rabbi Levik. We only know that he was executed by the Nazis, along with the Jews, in the Igren district hospital.

Rabbi Levi Yitzchak’s “anti-Soviet” (or rather, Jewish) activities inevitably incurred the wrath of the NKVD. In 1939, the Soviet Union conducted a population census. The questionnaire required individuals to specify whether they were believers or non-believers. Many feared speaking the truth and wrote “no.” After learning of this, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak delivered a passionate speech in the synagogue, stating that Jews must not conceal their faith in the One God. As a result, Levi Yitzchak Schneerson was summoned by the head of the NKVD in the city to confirm that there was no discrimination against believers. The rabbi refused to lie, and on March 28, 1939, the following resolution was issued:

RESOLUTION

Dnipro, March 28, 1939.

The Head of the 2nd Section of the 2nd Department of the State Security Directorate of the NKVD of the Dnipropetrovsk region – Lieutenant of State Security – PIVAK, having reviewed the operational materials on the Chief Rabbi of Dnipropetrovsk, Schneerson Levi Yitzhak Zalmanovich,

FOUND: Under the guise of religious activity, Schneerson L.Z. is conducting active anti-Soviet propaganda of a slanderous and defeatist nature. Having regular contacts with his son, the Chief Rabbi of Warsaw, a major agent of the Polish intelligence service, and with his close relative, the Chief Rabbi of Riga, Schneerson is engaged in organizational activities aimed at assembling a cadre of anti-Soviet clerical underground. He is suspected of espionage. Schneerson uses his weekly sermons in the synagogue to slander the Soviet government and its leaders. He is organizing large-scale financial aid for the families of repressed enemies.

Based on the above and considering the recommendations of the NKVD of the Ukrainian SSR regarding the arrest of Schneerson,

IT IS DECIDED:

To arrest Schneerson Levi Yitzhak Zalmanovich, born in 1878, a Jew, non-party, religious functionary, Chief Rabbi of the city of Dnipropetrovsk, and initiate criminal prosecution under Article 54-10, Part II.

Head of the 2nd Section of the 2nd Department of the State Security Directorate, Lieutenant of State Security (Pivak)

“Agreed”

Head of the 2nd Department of the State Security Directorate of the NKVD Lieutenant of State Security (Sapozhnikov)

At 3 AM on March 29, NKVD officers carried out a search at house number 13 on Barrikadnaya Street, seizing the manuscripts and books of the arrested rabbi. His interrogations yielded nothing. The prisoner was transferred to Kyiv, but the capital’s investigators were powerless. Levi Yitzhak Schneerson was returned to Dnipropetrovsk. His arrest shocked the city; synagogue board members Lyakhov and Shifrin died suddenly from the stress. On May 14, synagogue workers Abram Samoylovich Rogalin, Shlomo Vulfovich Moskalyk, and David Mordukhovich Perkas were arrested. David Perkas said: “Europe will not leave Schneerson’s arrest unaddressed, he is a very prominent figure…”

But the hope for European intervention proved futile. The investigation grew harsher, and the accomplices were interrogated by the deputy head of the investigation department, Chulkov, who was known as “The Terrible.” Under torture, Rogalin and Moskalyk signed confessions. Later, Rogalin stated that he had not been in control of himself at that moment. The methods of the investigation are reflected in Abram Samoylovich Rogalin’s appeal to the authorities:

“On May 14, 1939, I was arrested in Dnipropetrovsk, where I lived and worked. By a decree of the Special Council dated November 23, 1939, I was exiled for 5 years to the Kazakh SSR as a socially dangerous person.

After my arrest, I was held in the NKVD prison in Dnipropetrovsk, where they offered me to sign that I was a member of an underground religious organization that aimed to undermine Soviet power. The testimony they proposed I sign included accusations that our newspapers were lying about the Spanish War, about China, that Jews lived worse under Soviet power, and that life was better abroad, that there was nothing in the USSR, long lines everywhere, etc. To force me to sign these lies, they tortured me. They kept me in the investigator’s office, did not let me sleep, eat, drink, and did not allow me to use the bathroom.

Investigator Starchiy placed a bottle over my head and threatened to set my hair on fire with a lit candle, cursed me with shameful words, etc. Senior investigator Chulkov constantly instructed the investigators to torture me, exhaust my insides, break my ribs, and torment me until I signed everything. Exhausted by such methods to the point of losing consciousness, I signed everything they presented.

What happened to me is incomprehensible. Why? Who needed this? For what purpose? Everything I was accused of and forced to sign is a complete lie, slander, and injustice. I have never been part of any organizations, nor have I harbored any hostile feelings toward Soviet power. I am already an old man – I am 61 years old. Now I am in very poor condition, separated from my family, in horrible material and moral conditions, deprived of everything human, living in filth and hunger. Why should I endure this injustice? I ask you to take measures to restore my truth.

A.S. Rogalin, January 29, 1941.”

On August 11, the head of the NKVD of the Dnipropetrovsk region, Lieutenant of State Security Sedov, approved the “Indictment in the case No. 103129 for the prosecution of Schneerson Levi Yitzhak Zalmanovich, Rogalin Abram Samoylovich, Moskalyk Shlomo Vulfovich, and Perkas David Mordukhovich under Articles 54-10, Part 4.2 and 54-11 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR.” The indictment stated that the anti-Soviet activities of Rogalin, Moskalyk, and Perkas were carried out under direct instructions from Schneerson. A few days later, the rabbi was informed of the charges, which included his alleged connection with “the Jewish clerical community abroad,” the creation of an illegal network of funds to support the relatives of repressed Jews, and carrying out anti-Soviet propaganda under the guise of religious ceremonies in the synagogue and at home. The case was transferred to Kyiv, where it was concluded that “the materials collected for the trial in an open court were insufficient.” However, given the social danger posed by the accused, it was recommended that the case be submitted to the Special Council of the NKVD of the USSR, noting that some of the case materials “contained data that could not be used in the court session.”

On November 23, 1939, L.-I. Schneerson and others were sentenced by the Special Council to five years of exile in Kazakhstan. Repeated appeals from the families of the convicted, citing poor health and intolerable living conditions, went unanswered. One of L.-I. Schneerson’s letters to L. Beria was also reviewed by the Special Council on May 14, 1941, and the request for a reconsideration of the decision was denied. In this letter, he wrote:

“I am an old man, 70 years old, sick… Must I suffer unjustly for the rest of my life?… I have served the Torah all my life.”

Rabbi Levi Yitzhak served his exile in the railway station village of Chiiili, located 128 km from the city of Kyzylorda, in the Tashkent region. He arrived in Chiiili in the winter of 1940. The conditions of life in Chiiili for Rabbi Levi Yitzhak and Rebbetzin Khana Schneerson are reflected in a letter from the rabbi to his children, written on March 11, 1943:

“My dear beloved children! A few weeks ago I wrote to you. Not waiting for your letter, I am writing again. I have been living here for almost 4 years, and mother came to me 2 years ago for Passover… All our belongings: blankets and the like – were left at home, and we have nothing, no means of existence. We are alive, thank God, but our health is very weak, and we often fall ill. Oh! How I would like to be with my children in my old age, but we are among strangers, there are no acquaintances. I ask you to write to us immediately upon receiving this letter about your health and how you are living, and also to send us parcels: clothing – underwear and warm clothes, cloth for suits, also shoes – for me (size 43) and for mother (size 38), and so on, as well as food parcels.

We eagerly await your letter. I kiss you tightly, your father, Levi.

Greetings from mother. In the next letter, she will also write.”

Rebbetzin Khana did everything she could to ensure her husband could live and work under these conditions. There was no ink or paper, so she made ink from herbs, and in exchange for paper, she gave up the most necessary things. Thanks to this, Rabbi Levi Yitzhak was able to continue his brilliant commentaries on the Torah, known as “Likkutei.” During these hard years, Rabbi Levi wrote a series of books, later published: “Likkutei Levi-Yitzhak” – commentaries on “Tanya” and “Zohar,” and “Torat-Levi-Yitzhak” – commentaries on the Talmud.

After Levi Yitzhak’s death, his faithful Khana did everything to preserve and send his works to America. In one of his articles, Rabbi Shmuel Kaminezki wrote:

“Perhaps now it all seems simple and commonplace. But at that time, it was heroism. By doing so, she did more than the wife of a rabbi, and her act should serve as an example of selflessness and devotion to the Great Cause. Today is not such a time, and we are not required to have such self-sacrifice. The life and actions of the remarkable Rebbetzin Khana, the anniversary of whose death is observed on 6 Tishrei, continue to serve as an example: how in the most difficult and complex situations, one should not lose heart and not give up… The name ‘Khana’ contains the first letters of three important mitzvot for family life. The great woman proudly bore this name. We will always remember her.”

In April 1944, the rabbi and his wife were allowed to move to Alma-Ata. There were many Chassidim there, and during the first Shabbat, the rabbi prayed in a minyan on the outskirts of the city. The harsh conditions of exile took their toll. His old ailments worsened. On the night of 20 Av 1944, he woke up and asked for water to wash his hands. When the water was brought, he said: “We need to move to the other side.” These were his last words. He died on the 20th day of the month of Menachem Av in 5704 (1944) in Alma-Ata and was buried in the local Jewish cemetery.

His grave in the Jewish cemetery of Alma-Ata became a place of reverence.

Rabbi Levi Yitzhak Schneerson was rehabilitated in 1989.

In 1995, a three-volume biography of Levi Yitzhak was published in the USA and Israel.